Democracy Newsletter: September 2023 By Steve Zolno  Source: Vecteezy Source: Vecteezy Recently a Georgia teacher was fired by her board of education for reading a book to her fifth-grade class that the board considered controversial. The book was a popular children’s title: My Shadow Is Purple. A grandmother of one of the students approved of the firing, stating that it is up to parents, not teachers, to teach “cultural fads” to their children: “I want the parents to be parents and the teachers to teach.” (“Georgia teacher fired after reading book on gender to fifth-grade class,” Adela Suliman, The Washington Post, August 19, 2023.) Book banning in schools and libraries is increasing, with over 1,600 known incidents last year alone. (“Attempts to Ban Books are Accelerating and Becoming More Divisive,” Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth Harris, The New York Times, September 16, 2022.) The nature of what is taught also is being challenged. In Florida, current policy requires that children be taught about the “benefits” of slavery. (“Protesters Decry Erasure, Rewriting of Black History, from Florida Schools,” Democracy Now, August 17, 2023.) In Arkansas, advanced placement African American studies now are banned in high schools. (“Arkansas Orders Credits be Withheld for AP African American Studies in High School,” Democracy Now, August 16, 2023.) These and similar curriculum changes are increasing in many states. They add a new urgency to the perennial argument about what is teaching and what is indoctrination. Taking a step back and considering the purpose of education in a democracy might provide us a clearer perspective about the direction we want education to take. None of us would disagree that it is essential for children to learn basic skills to navigate life. Nor would we argue against vocational training required to move students toward their chosen career. But beyond that, what are the skills they need to maximize their ability to succeed? Our world is one of diverse individuals. No two of us are the same. In our schools, workplaces, and everyday lives, we encounter a wide variety of people with whom we need to work toward common solutions to the problems that confront us. We want recognition and acceptance for who we are, but many people from all backgrounds believe they never receive the recognition that is their due.  Source: Wikimedia Source: Wikimedia In the 1960s, segregation was a dominant practice in the South. Homosexuality was considered a mental disease in the US, a view even promoted by mainstream psychology. TV programs — including commercials — were dominated almost entirely by the presence of straight white Americans. This was the model unthinkingly promoted by our media and educational system. There has been a growing awareness of the horrors perpetrated upon those who didn’t fit the predominant idea of what an American should look and act like, and a greater understanding of what it means to be human slowly has awakened in this country. Many people have begun to realize that the value of human beings does not depend on their race, religion, sexual orientation, or other personal factors, but that encountering people as the unique individuals they are benefits those on both sides of the encounter. Unfortunately, many people still judge others based on their personal characteristics rather than their value as an individual. Yet an ability to work and live with others remains an essential element of success in all areas of life, unless we measure success by an ability to impede others based on what we don’t like about them. But those who do this are distracted from focusing on their own progress and success. Real education enables us to expand our horizons — to understand others and the world better and engage with them as they are, not as we imagine them to be. Progress in every area of knowledge — from science to geography to math to psychology — depends on encountering and learning to understand the world as we find it. The same principle applies to our willingness to understand individuals who compose much of the world with which we engage every day. It is not up to me to determine how or who you should be. If our approach is one of openness to who and what we encounter, our model of the world will expand as will our knowledge and wisdom. For those who believe that education is preparation for life, learning is an ongoing process of continually expanding our horizons. We strive to understand the mistakes of the past so we don’t continue making them in our own lives and times. Real education embraces the diversity and beauty of the world and people that surround us. This is the most essential element in our ability to function more effectively in every area of our lives. (For further reference, see In Defense of a Liberal Education by Fareed Zakaria, 2015, Norton Press, or my 2018 talk at the Commonwealth Club: “Do We Learn from History?”) Steve Zolno graduated from Shimer College with a bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences and holds a master’s in Educational Psychology from Sonoma State University. Steve has founded and directed private schools and a health care agency in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is the author of six books Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the email list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment.

0 Comments

Democracy Newsletter: August 2023By Robert Katz  By OpenIcons via Pixabay By OpenIcons via Pixabay We’re all aware of slippery slope arguments: If A, which is not so bad, is allowed then B, which is terrible, will surely follow. While such arguments are sometimes valid, they should be used sparingly. Thrown around indiscriminately, these arguments can lead to paranoia and polarization, warning of dire consequences from the adoption of reasonable measures. If we have universal background checks, next thing they’ll be confiscating our guns. Many people and groups reacted to the recent US Supreme Court decision in 303 Creative v. Elenis with a slippery slope framing. That was the case of the web designer refusing to do websites for gay weddings, with the court's conservative majority siding with the web designer. The ACLU had this to say after the decision came down: “The Supreme Court held today for the first time that a business offering customized expressive services has the right to violate state laws prohibiting such businesses from discrimination in sales. The Court’s decision opens the door to any business that claims to provide customized services to discriminate against historically marginalized groups.” Does this case really “open the door” for the kind of wholesale discrimination that the ACLU statement conjures? Let’s take a closer look at the decision. Briefly, the case arose when a Colorado web designer, Lorie Smith, decided she wanted to get into the wedding web design business, but did not want, because of her religious beliefs, to design websites for same-sex weddings. At the time the case was filed, she had not yet designed wedding websites, but courts allow preemptive lawsuits challenging a law when there is a real threat of prosecution for exercising First Amendment (speech) rights. Here, the state of Colorado, under its anti-discrimination laws, had taken legal action against a baker who refused to make custom wedding cakes for gay couples, and admitted it would go after Smith for her no-gay-weddings policy. Because Colorado had yet to act against Smith, her lawsuit was tried on the basis of stipulated facts — i.e., facts that both parties to the lawsuit agreed were true. One of those facts was that Smith’s web designs would be “expressive in nature,” designed “to communicate a particular message.” Another fact was that Smith would not otherwise discriminate against gay customers: if a person who happened to be gay was opening a restaurant and wanted her to design the website, no problem.  Dani Franco via Unsplash Dani Franco via Unsplash And in fact, Smith and Colorado agreed about most of the operative legal principles. Colorado conceded that when Smith created a website, she could not be forced to say anything that was against her beliefs. More generally, both parties agreed that Colorado’s anti-discrimination law did not dictate what goods or services a business sold, but only who it sold to. An analogy raised in the briefs is of a store that sells greeting cards. Under Colorado’s anti-discrimination law, the store could not refuse to sell cards to gay people or Jews. But neither could it be forced to sell cards that celebrate gay weddings or bar mitzvahs. So, under Colorado’s reading of the law, Smith was entitled to create only wedding websites that affirmed a traditional view of marriage. But she could not refuse to create such a website for a gay couple. In other words, if Smith offered to create a website celebrating the marriage of John and Craig, with a banner across every web page that said, “Marriage is the sacred union of a man and woman,” she wouldn’t be violating Colorado law. What gay couple in their right mind would want to avail themselves of such a website? Even under Colorado’s reading of its law, Smith would be able to effectively withdraw from the gay wedding website market. Of course, you can worry that maybe the next case will expand the definition of “expressive activity” protected by the First Amendment. But the Supreme Court majority, in all fairness, did limit its decision to the situation in which a person is creating a work of expression in words, pictures and video, which is clearly protected by the First Amendment. There may be close cases where the dividing line between speech and conduct is not entirely clear. But if a plumber refused to serve a gay person claiming his plumbing is an act of creative expression, the likely judicial response would be solvuntur risu tabulae, which is Latin for “you gotta be kidding me” (actual translation: “the case is dismissed amidst laughter”). Others may try to claim that a refusal to serve gay people is protected expression as part of their freedom of association. But this kind of argument has been soundly rejected by the Supreme Court, which so far has upheld public accommodations laws such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act against free-association claims. It seems unlikely that even the current conservative court would want to disturb that particular hornets’ nest. The law is often engaged in balancing competing values, both of which are important — such as in this case, free speech and anti-discrimination. The rule of law thrives on distinctions, sometimes very fine ones. This most recent case makes a modest concession to free speech over anti-discrimination policy, a concession that, given what the parties were arguing, doesn’t seem to be all that consequential. We have to remain vigilant that the next case doesn’t expand the scope of that concession in a way that more seriously undermines discrimination laws protecting gay people. But let’s not exaggerate the importance of a decision that doesn’t make a lot of practical difference by hoisting the slippery slope flag. Robert Katz served as a staff attorney and supervising attorney at the California Supreme Court from 1993 to 2018. Before that, he was in private practice representing public agencies, and worked as a newspaper reporter covering local government in Santa Cruz County. Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the email list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter, July 2023By Steve Zolno Many anthropologists who have looked into the structure of human societies believe that our earliest origins point to humans being democratic. (See, e.g.: Francis Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order, 2011, p. 53: “For bands and tribes, social organization is based on kinship, and these societies are relatively egalitarian.”)  Acropolis — Photo by Steve Zolno Acropolis — Photo by Steve Zolno As bands turned into tribes and then nations, a central authority figure emerged who was far removed from the immediate lives of most members of society. That was an individual or group that created and enforced the rules by which people — other than themselves — were required to live. Those who came into power usually sought to retain it for themselves and their families. An exception was the early experiment in democracy in ancient Greece, which ultimately failed. People submit to authority because they are protected by living in large societies rather than trying to survive on their own. To use Hobbes’ famous phrase, in a state of nature life is “nasty, brutal and short.” (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, Chapter XIII, Part 9: “Of the Natural Condition of Mankind as Concerning Their Felicity and Misery.”) His view, in a time before modern democracy, was that any state is preferable to none. Perhaps it is fair to say that most of us seek the comfort of living in a society, but when we believe ourselves oppressed, we seek freedom. Thus we are both social animals and people with an essential belief in our value as individuals. The way this plays out in our everyday lives is that we don’t want to be isolated from society but also seek to express our individuality. Every political movement — ancient, modern and those in between — can be seen in this light. Many countries that seemed to have been moving toward democracy over the last century have become mired in autocracy, while many individuals under autocratic rule have expressed their desire for freedom. In the US, which was founded on overthrowing what was considered an authoritarian regime, there still are many who are convinced that the current government is oppressive and does not recognize their essential needs.  Washington Attacking the Hessians — Emanuel Leutze Washington Attacking the Hessians — Emanuel Leutze We might ask if it is possible to create a government that satisfies both of our desires for stability and freedom. That was the intent of the US founders as they wrote the Constitution in response to a failed attempt at government under the Articles of Confederation in the years after the Revolutionary War. If human nature mandates we dwell on what is missing in our lives and country, rather than the direction we want to go, there may be no type of government that can satisfy our desire for stability and freedom at the same time. If, however, we stress educating our population about how responsibility on the part of citizens is required to sustain the benefits of democracy for everyone, it may be possible to work toward a truly participatory type of government. The essential principles of such a system cannot be written into law; they need to be understood by the majority of individuals who support real democracy based on compromise as well as insisting on one’s rights. Realizing that my freedom is limited by where it impinges on that of others is the most essential step to protecting me and others at the same time. Freedom and rights as we usually understand them fail to provide the accountability that makes democracy work. We operate as much by habit as principle. Our custom of considering only our individual needs fails to recognize the poorly functioning democracy to which it contributes. Dialogue with others toward workable solutions at all levels — in government, organizations, schools, families and our personal lives — is our only hope for maintaining democracy. The course of democracy in the United States will largely be determined by our upcoming elections. The most essential principle of democratic rule of law is holding each of us responsible for contributing to the type of country that respects the rights and dignity of everyone. If a candidate or party that promotes this principle prevails, American democracy will likely be preserved; if those prevail who do not believe that this principle applies to them as well as everyone else, our democracy likely will become another failed experiment. Steve Zolno graduated from Shimer College with a bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences and holds a master’s in Educational Psychology from Sonoma State University. Steve has founded and directed private schools and a health-care agency in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is the author of six books. Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the email list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter: June 2023By Robert Katz

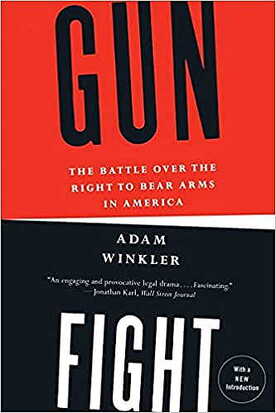

The explanation for this bit of judicial nonsense is to be found in the Supreme Court’s decision last term, New York Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen. Back in 2008, on a 5–4 vote, the Court decided that the Second Amendment right was an individual right to self-defense, not merely the right of states to maintain militias. That case, District of Columbia v. Heller, acknowledged that some gun-control measures would nonetheless be constitutional, but left unanswered the question of how their constitutionality would be determined. The federal courts of appeal after Heller devised their own two-step constitutional test that went something like this: First, the court would decide whether the gun-control measure infringed on the Second Amendment at all, using history to determine whether such gun-control measures were in practice at the time that the Second Amendment was adopted. Second, if history did not answer the constitutional question, then courts would employ a balancing test: Given the nature and extent of the intrusion on gun rights, was the government’s interest in protecting public safety sufficient to justify the law’s intrusion? Under this two-step test, the Fifth Circuit had previously upheld the constitutionality of a law prohibiting domestic violence perpetrators from owning guns. In Bruen, the court threw out Step Two. The only question that needs answering, according to the majority opinion, is whether the gun-control measure at issue has a sufficiently close historical analog to the laws in force at the time the Second Amendment was enacted. How close? The court didn’t make that clear. But the new method of constitutional reasoning that the court prescribed, based solely on history and historical analog, led directly to the preposterous decision that domestic violence abusers had the constitutional right to own guns. Justice Thomas, writing for the court in Bruen, argued that we needed no such Step Two balancing test because the Second Amendment already incorporates a balance “struck by the traditions of the American people.” But what does that mean? If you’re balancing the dangers posed by guns with the right to self-defense, then that balancing will look drastically different in 2023 than in 1789. The latter was a society in which most people lived in small towns or farms, there were no cities with a population greater than 35,000, there were no professional police forces, firearms required reloading with every shot, and the biggest dangers were from belligerent Indians and recalcitrant slaves. To state the obvious, we live in a different world, one of epidemic gun violence in a highly urbanized society, where weapons load automatically, where every week brings news of mass shootings, and where gun violence — homicides and suicides — is the leading cause of death in children.  But even in bucolic early America, society was planted thick with laws controlling the use of guns. As UCLA Law Professor Adam Winkler recounts in his book Gun Fight, there were laws requiring guns to be given up to the authorities in times of war. Concerns with gunpowder igniting fires caused some jurisdiction to prohibit the storing of guns inside homes or other buildings. There were laws forbidding sale of guns to Indians or free Blacks. There were laws routinely requiring a town’s adult male populace to report with their guns to be inspected to see if they were in good working order. In the late nineteenth century, shortly after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, in the so-called wild West, frontier towns like Dodge City or Tombstone forbade gun possession within the town limits. The guns had to be left with the sheriff or in the outskirts of town with their horses. These measures resulted in surprisingly low murder rates, and researchers have concluded that “many more people have died in Hollywood westerns than on the real frontier.” (Winkler, p. 164) The lesson we can draw from this history is not a precise model of the kind of gun legislation we need today, but rather the general principle that gun rights were always embedded in the social and legal order that limited dangers posed by gun ownership. Indeed, the very wording of the Second Amendment, with its prefatory clause “a well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state,” preceding the declaration of the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” strongly suggests that the framers of the Second Amendment envisioned a version of gun rights that was consistent with, indeed subordinate to, public safety. But if we follow a strictly historical model much commonsense and widely supported legislation — background checks, keeping guns out of the hands of the mentally ill, licensing gun dealers, prohibiting ex-felons from buying firearms — all may be in constitutional jeopardy because none of these laws existed at the time of the Second Amendment’s adoption. Democratically elected representatives have no greater responsibility than to keep their constituents safe. Perhaps the US Supreme Court will eventually overturn the Fifth Circuit’s decision protecting the gun rights of domestic violence abusers. It may clarify Bruen so as to make the decision more intelligible and more workable. But to have a court with clear ideological bias consult 18th and 19th century statute books to decide whether 21st century gun-control laws will be allowed to stand is an appalling prospect and a usurpation of democratic self-government. Being clear that this is an unacceptable state of affairs is the first step to changing it. Robert Katz served as a staff attorney and supervising attorney at the California Supreme Court from 1993 to 2018. Before that, he was in private practice representing public agencies, and worked as a newspaper reporter covering local government in Santa Cruz County Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the email list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter: May 2023By Steve Zolno Hopefully you have seen Rob’s post from last month about fair treatment for transgender individuals. For me, that brings up the question of whether laws alone can establish fairness, or we need to look beyond them to have the type of society in which we want to live. Our laws are based on a morality that we assume members of our society have in common.  Image: Succo/Pixabay Image: Succo/Pixabay A difference between us and other creatures is that we recognize a need for consistent behaviors. From the earliest times, people created rules, and then laws, to enable them to live together. This is the basis upon which societies are built. Laws are an attempt to provide guidelines for acceptable behaviors and consequences for violations. But autocratic leaders often are immune to following them. Because there have been laws in all societies as far back as we can see, we must assume that there are people whose actions fall outside their moral codes. Some questions we might ask:

Laws became codified in early societies, such as those of King Hammurabi of Babylon, which are the oldest complete codes yet discovered. Those codes — and similar ones from that time — provided specific punishments for infractions, including the famous phrase “an eye for an eye.” They also stated that their moral principle was “to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak.” In democracies, laws are written by representatives of the people and are assumed to apply equally to everyone. As I’m sure you have noticed, there is no end to our lawmaking process. New laws continually are being created and old ones revised to fit circumstances that previously were not considered. This creates careers for lawmakers. But are we clear about the intent of our laws? Do we want to punish people for violations, to create a better society, or both? Will we ever get to a point where we have enough laws to guide us, or is there another approach that might help us realize our intent more efficiently? Within each of us lies an ideal of how we want to be treated, and thus how people should treat others, if we are to live together successfully. Laws in democracies are an attempt to approach this ideal. But as we all have seen our laws — and each of us — often fall short.  Image: Tumisu/Pixabay Image: Tumisu/Pixabay What if our democracies emphasized working together toward common goals rather than competition? What if our educational system encouraged responsible behavior toward others? What if in our everyday interactions we focused on the value of other human beings? Many of our laws assume the worst about people: that they are capable of operating only from the view of their own limited self-interest. But when I begin to see my self-interest tied to that of others, and operate from that principle, a win-win outcome may be possible. I begin to operate from a view that seeks outcomes that benefit us both. You might be thinking: “Human nature is basically selfish. No one would be willing to take that view.” That would be a reasonable assumption based on our experience. But perhaps, just in our own lives, we could begin to choose to look at others more as partners than as adversaries. Perhaps we could take the first step toward creating the morality we hold in our minds, at least in our own interactions. You may consider it naïve to expect changes in our basic societal perceptions. Slavery, and then segregation, once were assumed to be essential to the functioning of a large segment of society, and now most of us realize that those institutions, and the views on which they were based, no longer serve those on either side of the divide. Our society once held homosexuality to be a mental disease, but observation in place of prejudice eventually upended that view. And though many see transgender individuals with suspicion, or even contempt, our society may be coming to the realization that all sexual orientations and gender identities are valid. Many intolerant viewpoints once backed by laws were overturned as we opened our minds and hearts and their error became apparent. Even during the times in which these mistaken views dominated our culture, there were those who saw beyond them and worked — privately and publicly — to overturn them. Perhaps there are those in our day who see that all views and laws based on blame and recrimination only lead to the perpetuation of the hate we want to eliminate. Of course some laws are needed: Serious anti-social behavior must result in isolation of the perpetrator, but our ultimate goal must be reintegrating the individual into society rather than sticking a label of blame on a person for life. We don’t need to change the world to alter our perceptions and interactions. We can take the view that seeing others as not quite as human as ourselves impedes the ability of our world — and each of us — to move forward. We can consider the possibility that how we see people may be only half-truths, and perhaps the other person also is a human being trying to succeed in a competitive world. Perhaps there is more to others — and of us — than we usually allow ourselves to perceive. The type of morality by which we live affects us personally. If we hold others in esteem we have a personal experience of esteem; if we hold others in contempt we experience contempt. So perhaps when engaged in conflict we can refocus on a direction that suits us mutually rather than only our side. Perhaps as we interact in a way that considers the needs of all we can find a viable path forward. Perhaps as we do this, we will get less of what we think we want but more of the peace of mind we seek. And perhaps we will begin to experience more of the freedom that democracy promises. Steve Zolno graduated from Shimer College with a bachelor’s degree in Social Sciences and holds a master’s in Educational Psychology from Sonoma State University. Steve has founded and directed private schools and a health care agency in the San Francisco Bay Area. He is the author of six books. Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the email list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter: April 2023 By Robert Katz The treatment of transgender people is one of the most active fronts in our never-ending culture wars. Any nuance gets lost on both sides of the debate. At the risk of being caught in the crossfire, this post attempts to formulate a sensible framework for understanding this issue. My starting point is the affirmation of two principles. First, people should be able to express their gender identity as they wish, not in conformity with other people’s ideas. That principle is rooted in the fundamental right to express oneself linked to the First Amendment protection of freedom of speech. Second, gender dysphoria, the strong sense of belonging to a gender other than the biological gender into which one was born, is real. The causes of gender dysphoria are not well understood, but seems to have a physiological basis, at least in some cases. From this emerges the principle that people experiencing gender dysphoria should be given “reasonable accommodation,” a term that comes from the law of disability discrimination. Discrimination on the basis of disability cannot be addressed by treating disabled people the same as the so-called able-bodied. Schools, workplaces, and other public spaces must reasonably adapt to their needs in order to give them an opportunity to participate in society and reach their full potential. So it is with transgender people: we are obliged to reasonably accommodate them so they can live in alignment with their gender identity and still be fully functioning members of society, countering a tendency to marginalize them due to their unusual physical circumstances. The recent spate of legislative proposals in Republican states are rooted in denial of these principles. Their animating idea, genuinely believed in or professed out of political opportunism, is that the law should define people’s gender according to their biological sex “without regard to an individual’s psychological, chosen or subjective experience of gender,” as a recent South Carolina Republican resolution reads. According to an article in the New York Times, in addition to bathroom and sports bills, a new wave of over 150 anti-trans bills proposed in at least 25 states include bans on transition care into young adulthood, on drag shows, and on teachers using names or pronouns not matching students’ biological sex. As with other issues, like climate change, structural racism, and who won the 2020 presidential election, some Republican politicians hope to parlay evidence-free bias into a winning political strategy. Nonetheless, the affirmation of the two principles above don’t resolve all transgender issues. Inasmuch as the transgender agenda asks not merely for freedom of expression, but for societal accommodation and medical intervention, it raises a number of issues that can’t be dismissed as simply transphobic. For one, how do we know when medical intervention is appropriate, and what kind of intervention? Our answer to these questions may depend on how we interpret transgender demographic trends. According to one study of the U.S. population, 1.4 percent of 13- to 17-year-olds and 1.3 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds identify as transgender, compared with about 0.5 percent of adults. To what extent is this difference accounted for by the fact that trans-inclined adults have been inhibited by social pressure from living as their authentic selves, and to what extent is the difference an artifact of social influences to which people under 24 are exposed? If the later, then perhaps stricter protocols for medical intervention, particularly for minors, is called for. Then there are questions around which accommodations are “reasonable.” For example, while the issue of transgender competition in women’s sports has been amplified by right-wing hysteria, there are plausible arguments for placing some constraints on that competition. The ardently feminist Women’s Sports Policy Working Group, for example, although in favor of some transgender women’s participation in recreational sports, have raised concerns about the advantages that transgender women’s athletes who have gone through puberty as males may retain, and have proposed some limitations on their participation in girls’ and women’s sports at the competitive level. You may disagree with their position, but it isn’t reasonable to simply dismiss it as the product of bigotry. Questions about reasonable accommodation extend into areas of language. Using a person’s preferred gender pronoun seems to me unproblematic. But do we need to socially ostracize anyone who doesn’t use “pregnant people” and “people who menstruate” to refer to biological women? Do we all need to fall in line with the decision in some quarters of academia and the media to use “Latinx,” a term favored by only 4 percent of the people in the country who identify as Hispanic? The Republican wager that anti-trans legislation will have political benefits may pay off, at least in the short term. According to a 2022 Pew Research Poll, although 64% of respondents were opposed to discriminating against trans people in employment and housing compared to 10% in favor, they believed, 58% to 17%, that trans athletes should compete on teams that match their sex at birth, 46% to 31% that health care professionals should be prohibited from assisting people under 18 to transition, 41% to 31% that trans people should use the bathroom of the sex assigned at birth, and were evenly split on whether parents who help their children transition should be investigated for child abuse. And this gets to a reality not often acknowledged in liberal circles — that to many people, transgender is a strange phenomenon because it is far outside their personal experience. Prejudice stands ready to supply the answers where experience can’t. There is a tendency among some militant advocates to dismiss any questions and concerns about the accommodation of transgender people as simply transphobic. Transgender advocates may succeed in making certain spaces like universities safe for trans folk, and may intimidate some who express heretical opinions. But as the above survey indicates, they may not be able to translate their dominance in some corners of society into actual political power. And not only is the transgender project placed in jeopardy, but Republicans are using its unpopularity to thwart a progressive agenda that would address climate change, racial justice, and economic inequality. Persuasion on transgender issues will not be possible until advocates realize that at least some questions about the accommodation of transgender people are legitimate and should be addressed, even if they passionately believe that they have the right answers to those questions. Robert Katz served as a staff attorney and supervising attorney at the California Supreme Court from 1993-2018. Before that he was in private practice representing public agencies, and worked as a newspaper reporter covering local government in Santa Cruz County. Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter: March 2023An excerpt from Steve Zolno’s new book, The Pursuit of Happiness. “Available wherever books are sold” as of March 15, 2023  At the time of the founding of the United States, every other country was under autocratic rule. The word “democracy” had not been used for over 2000 years. That term, meaning “rule by the people,” came out of ancient Greece, while the Romans later used the word Libertas, or freedom, to describe what they considered an essential principle of their republic. During the US Revolution, most people thought only of overthrowing British oppression and had no idea about what would be the best way to govern the new nation. This is typical for revolutions. The US Founders were well-educated and mainly from upper classes. Many were slave holders, yet they considered themselves oppressed by the British King. They were inspired by such writers as the Englishman John Locke who insisted that people have the right to overthrow oppressive government, and the Frenchman Charles Montesquieu who proposed that a separation of powers of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government is needed to keep one branch from becoming too powerful. At first the US was a loose association of states under the Articles of Confederation. Eleven years later it became clear that a strong central government was required for the nation to succeed, and the Constitution was born. Since that time over 100 countries have tried to install democratic governments, many with limited success. One of the most famous phrases in democracy is from the Declaration of Independence. It states that human beings are entitled to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness.” These terms are not well-defined in the fairly short Declaration, but the phrase has inspired people for nearly 250 years to believe that these qualities are their due. We will briefly discuss each in an attempt to clarify what the writers may have had in mind. We might think the meaning of “Life” to be obvious. But does it simply mean a right to stay alive, or does it refer to a life of quality and recognition for the value of each individual? Most likely everyone who has been inspired by those words would agree it means the latter. And what is meant by “Liberty?” We can surmise that the term refers to an ability to determine the course of one’s own life rather than have major decisions decided by others. Of these three the phrase that seems to have the least clear meaning is “The Pursuit of Happiness.” This was the most fought-over. Did the US Founders intend for denizens of the new country to determine their own paths to the extent possible? Did they assume that the pursuit of happiness was equivalent to freedom? Most of us probably would agree that democratic governments are more likely than autocracies to afford people an opportunity to pursue happiness. Millions of refugees from autocratic regimes have sought to live in democracies since they came into existence. Those who live under autocracy seek democracy not only for political freedom but because many autocracies lack economic opportunity, and in many the bulk of the population is mired in poverty. But once we have secured our life and liberty, are we free to pursue happiness? And do those of us fortunate enough to live in democratic countries even agree about what happiness is? Is it the accumulation of goods, involvement in meaningful relationships, or is it freedom to pursue our own path? These are some of the directions that happiness could take. We might also ask if there is an underlying quality that unites our experiences of happiness that lends meaning to the term. And perhaps more importantly, do we have control over our happiness, or are we always at the mercy of the situations of our lives? Even within what we consider democracies, there are those who would move their countries in the direction of being more autocratic. If we want to preserve democracy it is essential that we identify and combat those elements before they become prevalent. A group of oligarchs attempted to seize power in ancient Athens, and the Emperor Augustus ended the Roman Republic. In the United States there was an attempt to overthrow the presidential election by an insurrection. Efforts by those of authoritarian minds and their followers always are a threat to “rule by the people.” But one person cannot overthrow a government without a large group of followers. So what is it in the human personality that seeks democracy when subject to autocracy, but for many, seeks autocracy when living under democratic rule? Is there a conflict within each person, or just different preferences among different people? Democracy and autocracy are determined not only by the government in a country or state, but by the nature of its institutions. A truly free country has a free press that explores and exposes shortcomings wherever they find them, including the government. A truly democratic country has a balance between branches of government so that no one person or group can dominate and deprive people of their rights. A country that intends to maintain democracy has educational institutions that train students in what democracy means. It creates a model for how individual freedom is built by encouraging free and creative expression. Its educational institutions not only train students in the lessons of the past but encourage them to consider how best to move democracy forward. They expose them to a variety of views so they can come to their own conclusions about how best to nurture democracy. Clarity about the nature of democracy and how best to preserve it is the greatest lesson our schools can impart. But above all, democracies that endure have the bulk of their population committed to the idea that “rule by the people” means a government that represents and serves all of the people. Countries where that understanding is not prevalent often have had their democracies overturned. We who live in democracies see autocrats around us trying to use their influence to permeate the globe. This applies not only to autocratic states, but to countries that pretend to be democratic while moving toward greater oppression. It can be seen in censorship of the press and manipulation of what students are taught. If we are to preserve our democracies, there must be a clear plan on the part of democratic governments to make a statement that autocratic rule is not permissible. This could include sanctions on leaders put in place on a scale of the degree of freedom a country provides and that hopefully do as little harm as possible to residents. The democratic freedoms of everyone worldwide are connected. If we abandon those who are oppressed anywhere, we are opening a gate for the spread of autocracy everywhere. Going back to the pursuit of happiness, the guarantee of democratic freedoms is an ongoing effort that always will be with us. There is an element in everyone that seeks models for how to act and another element that wants freedom to chart our own course. When we consider those we choose for our leaders, it is essential to determine if they are committed to the tenets of democracy, which include recognizing the value of each individual and an appreciation of the potential contribution of everyone. Leaders who denigrate others appeal to the autocratic side of our personality to gain support, and once in power demand allegiance to themselves — even from their followers — rather than to the principle of equal treatment for all. While we work toward our democratic ideals, we can focus on the happiness that democratic government allows us to pursue. If not, the most essential promise of democracy will have been wasted. Understanding what happiness really is and how best to bring it into our lives is not only a worthwhile pursuit but an indispensable element of making democracy work. Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Democracy Newsletter: February 2023By Robert Katz As we mark the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, I note that the supporters of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision revoking the constitutional right to an abortion, have sought to draw celebratory parallels between that decision and Brown v. Board of Education. This was the case that recognized the principle that “separate but equal” treatment of Blacks and Whites in segregated schools was incompatible with the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Like Brown, Dobbs overturned a foundational precedent that had been in force for decades, and according to anti-abortion proponents, established an important right — the right to fetal life — denied by the discredited precedent. The Dobbs opinion itself referenced Brown a number of times, and Mitch McConnell said of the Dobbs decision: “The Court has corrected a terrible legal and moral error, like when Brown v. Board overruled Plessy v. Ferguson.” But the differences between Brown and Dobbs far overshadow their similarities. There is the much-discussed issue of how these decisions used history. The Brown court refused to be bound by the views of those who ratified the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. The vast majority of those legislators almost certainly would have approved of racially segregated schools. In contrast, the Dobbs court found the fact that abortion was widely criminalized in 1868 to be decisive. Had Brown followed the Dobbs court’s method of constitutional reasoning, it would have upheld Jim Crow schools.  Ian Hutchinson via Unsplash.com Ian Hutchinson via Unsplash.com However, I would like to focus on another critical difference — the conditions under which the precedent was overturned. In Brown, the court was undoubtedly influenced by the changing attitudes toward race in the US. Having just fought a war against an enemy whose core ideology was extreme racism, and in which Black Americans served valiantly, the post-war period saw a reevaluation of racial attitudes. According to polls undertaken by the National Opinion Research Center, in 1942, only 42 percent of people believed that Blacks were the intellectual equal of Whites. By 1956 that number had risen to 78 percent. In 1942, 30 per cent believed that schools should be integrated; the percentage rose to just under 50 in 1956, and to over 60 per cent by the 1960s. The Brown court was not only influenced by changing attitudes toward race, but as these statistics suggest, helped to further catalyze that change by putting its imprimatur on the doctrine of racial equality. Reality has a way of intruding, however belatedly, on myth, and the myth of Black inferiority gradually gave way to the reality of Black equality. By contrast, views on abortion remained fairly constant in the 30 years prior to the Dobbs decision. According to the Pew Research Center, 61% of those polled in 2022 believed that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, about the same percentage as those polled in 1995, with some fluctuation. Unlike racial attitudes, there was no corresponding shift in attitude away from abortion rights. The differences between a 15-week-old fetus and a newborn infant are significant, physiologically and neurologically. One can argue about the moral significance of those differences, but nothing we have learned about the science of fetal development since the abortion right was recognized in Roe has been cause to reevaluate one’s position on abortion.  What made Dobbs possible was not shifting societal attitudes on abortion but a decades-long campaign on the part of right-wing politicians and their attorney counterparts to appoint antiabortion judges to the United States Supreme Court. As has been much discussed, the Federalist Society, since its inception in 1982, has played a preeminent role in choosing federal judges. After their initial disappointments in the appointments of moderate Sandra Day O’Connor, sometimes moderate Anthony Kennedy and the downright liberal David Souter, the Society developed a sure-fire vetting process, generally recruiting from among their own ranks. Since the appointment of Clarence Thomas by George H.W. Bush in 1991, no Republican president has appointed anyone not affiliated with and/or blessed by the Federalist Society. When it came to the Trump presidency, the predominance of the Federalist Society in choosing judges was on full view. In exchange for social and religious conservatives overlooking Trump’s many personal failings, he outsourced the vetting and selection of judicial candidates to the Society. Aided by Mitch McConnell’s infamous constitutional hardball, Trump got an appointment that should have been President Obama’s, then a second appointment with Justice Kennedy’s strategic resignation, and a third with Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s passing on the eve of the 2020 election to cement the Dobbs majority. So, the success in overturning Roe, unlike the success of Brown, is not a story of society’s evolution on the abortion issue, but of consummate political engineering to change the high court’s personnel. It is said that the process of judicial decision making is fundamentally different from politics — that judges must at least appear to be interpreting rather than making law. But it is clear that the overturning of Roe did not really occur in the judicial chambers of the Supreme Court, but upstream, in the precincts of the Federalist Society and the decisions of Republican presidents and senators. And unlike Brown, a decision that is now almost universally accepted and praised, it is most unlikely that Dobbs, a decision that never even acknowledged the enormous burden that abortion bans place on women’s liberty, will ever enjoy such widespread acceptance. Its legacy instead is likely to be the further politicization of the High Court and degradation of its reputation. Given the right-wing playbook of exerting political power to appoint ideological judges, there likely will come a time when the Democrats will be in a position to answer politics with politics in the form of increasing the number of members on the High Court or requiring that Supreme Court justices are rotated out of the court after a term of years. Whatever form it takes, Democrats will follow the path laid out by Republicans that the key to success in the Supreme Court is to choose, by whatever means are expedient, the right Supreme Court justices. Robert Katz served as a senior attorney and supervising attorney at the California Supreme Court from 1993 to 2018. Before that, he was in private practice representing public agencies, and worked as a newspaper reporter covering local government in Santa Cruz County. Sources: Mitch McConnell quote: https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/09/opinions/scotus-dobbs-faulty-comparison-brown-snyder/index.html National Opinion Research Center survey: https://www.norc.org/PDFs/publications/NORCRpt_119.pdf Public Opinion on Abortion (Pew Research Center): https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/public-opinion-on-abortion Federalist Court (Slate.com): https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2017/01/how-the-federalist-society-became-the-de-facto-selector-of-republican-supreme-court-justices.html Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. Two Types of LeadersIn our time, and all times, there have primarily been two types of leaders. Early in the human story, according to most anthropologists, members of small tribes participated in decisions about the rules they would follow and who would lead. Survival depended on leaders considering the best views of tribe members as they forged a path forward. As tribes grew into nations, a central leader or ruling family emerged. This provided an enhanced chance of survival because large social units guarantee greater protection and security. But the needs and priorities of people were sublimated to the whole. They were forced to give up individual freedoms and lost the ability to provide input on the rules that would govern them. Most autocratic nations have a history of attempted — and often failed — rebellion because of the impulse toward freedom and recognition within every human being.  Parthenon photo by Hans Reniers/Unsplash.com Parthenon photo by Hans Reniers/Unsplash.com In Athens around 600 BCE, some rulers realized the disadvantage for those at all economic levels of growing inequality. Small farmers needed to borrow from the wealthy and often could not pay their debts during poor harvests. The result was perennial indebtedness that benefited no one. This led to a reversal of the debt system. More members of society were allowed to participate in the rule making process. Only those chosen as community leaders were included in decision making, but that challenged the idea of an absolute ruler. This was the beginning of democracy in ancient Greece and Rome. But both struggled between democratic and autocratic systems, with some leaders advocating for government by the people and some seeking to promote a single ruler or themselves. Much later, in 1215, a group of English nobles forced King John to sign the Magna Carta. This was the origin of limits to absolute authority that began the democratic thrust in the Western world. Since then there has been a conflict between leaders who champion democracy, which means “rule by the people,” and leaders who promote the dominance of some over others. The debate about whether people are capable of governing themselves goes back at least to ancient Greece, where both Socrates and Aristotle feared rule of the mob. They favored enlightened rulers who would hopefully treat people fairly. In the US, since its founding, there has been a gradual movement toward treating people equally or by “rule of law,” despite huge setbacks and resistance. The most famous phrase in democracy is the part of the Declaration that states “all men are created equal.” But that phrase is easier to state than to follow and not all leaders — even in countries that consider themselves democratic — have been guided by it. Leaders who promoted democracy were ahead of their time. They focused on the long-term perspective that it only can exist where everyone is considered valuable and treated equally. Their hope was to build a more inclusive world and end the need for war. Abraham Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson come to mind. But while we may believe that we, and those we think of as being like us, are valuable human beings, there always have been those who consider themselves and their own group more deserving of privileges than others. When looking at history, some basic themes emerge. Truly democratic leaders remain committed to the principle of respect for every human being. They may forget this principle at times as they engage in partisan activities, but ultimately come back to it. They are found at all levels of leadership — from local organizations to national government. Effective leaders focus on working with others toward solutions. Ineffective leaders focus on blaming others for their society’s woes or lack of progress. Effective leaders have — and share — a long-term vision of how to move toward a world where the rights of all are respected. Leaders of an autocratic mindset focus mainly on the short-term perspective of how they can allow themselves and their cohorts to remain in power. No one can come into a position of leadership — or stay there — without popular support. Democratic leaders have compassion and concern for the lives of everyone which is expressed in their actions. Autocratic leaders only receive the support of those who believe that some should dominate others. Leaders who believe in democracy understand that human beings, though imperfect, need to bond together to get their needs met and promote policies toward that end. Your comments and thoughts always are welcome. Also, don’t forget to look at our blog site: renewingdemocracy.org Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment.  On December 5 we had a special presentation by Claude Fischer, sociology professor at UC Berkeley, about his book Made in America (2010, University of Chicago Press). The intent of the book is to chronicle the reality of America’s past based on the actual lives of its people, rather than in broad historical generalities. This was done by examining records that were written by or about those who dwelled in what now is the United States going back to colonial times. A quote from Page 5 summarizes the intent of the book:

The question the author aims to answer is: “How has American society changed or not?” since its founding. Some myths that exist in our time may not be accurate, such as the ideas that we have turned from religion over the years, or we have become more violent, or that we are less caring toward each other than we once were. He states that what has made the US unique — and still does — is the shared idea that we are individuals who participate voluntarily in community and that individuals succeed through a voluntary — not forced — commitment where each does his or her share to advance the whole. Early in our history most Americans were dependent on others as indentured servants, women, or children. Only white, property holding, men had “competency,” or autonomy and independence as others depended on them for sustenance. Over time, more Americans were able to participate as productive members of society. In earlier times, life was more of a struggle for the average person than it is today. People had many children, and the childhood death rate was high. Over time, with improved hygiene and general prosperity, people lived longer, which freed them to pursue improvements in their lifestyles. Average Americans also experienced more security over time with the gradual introduction of more government intervention to protect working class individuals. Anti-trust and labor laws were enacted around the time that the 19th turned into the 20th century. After the Great Depression resulted from broad market over-speculation, more government programs were put into place to prevent people from spiraling into intense poverty, such as work programs, and to protect workers in retirement, such as Social Security. Banks were more regulated to prevent them from speculating with the funds of their customers. Persistent poverty then was attacked by legislation such as Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s, which also saw the enactment of the Clean Air and Civil Rights Acts. Over time, with greater mass buying power, more goods became available that people eventually took for granted. In Colonial times, clothes for most were handmade and worn until they became threadbare; beds, tables and chairs were considered luxury items. By the 20th century, electric lights, cars, and telephones were considered necessities even by those considered to be at the poverty level, as were computers and cell phones in the 21st century. Toward the end of the 20th century, Americans lived less in the public sphere and retreated more into private life as they gathered around their TV sets with their families. Self-improvement, once the realm of only the wealthy and literate, became the vogue for average Americans, as many became familiar with the views of Freud and Benjamin Spock. Thus, based on research into the lives of Americans over the first two-and-one-half centuries a few trends become clear:

One more important aspect of studying and surveying our culture is the issue of whether greater general prosperity over time has led to greater happiness. Results show almost universally that “average American happiness … stayed flat. … Beyond a basic level … more money does not make people happier.” Of course, this is not only an American phenomenon, but if accumulating greater wealth and possessions is not the key to happiness, with the US being the richest country on Earth (according to the World Bank), one must wonder what is the key. Perhaps that realm lies in another area of study. Your comments and thoughts always are welcome. Also, don’t forget to look at our blog site: renewingdemocracy.org Please recommend this newsletter to people who you think might appreciate it. If you want to be added to the list to receive each new newsletter when posted, fill out our contact form and check the box just above the SUBMIT button. You may also use that form to be removed from our list.

Visit our Books page for information about purchasing The Future of Democracy, The Death of Democracy, Truth and Democracy, and Guide to Living In a Democracy. Click ↓ (#) Comments below to view comments/questions or add yours. Click Reply below to respond to an existing comment. |

5th edition now available 5th edition now available

Steve ZolnoSteve Zolno is the author of the book The Future of Democracy and several related titles. He graduated from Shimer College with a Bachelor’s Degree in Social Sciences and holds a Master’s in Educational Psychology from Sonoma State University. He is a Management and Educational Consultant in the San Francisco Bay Area and has been conducting seminars on democracy since 2006. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed